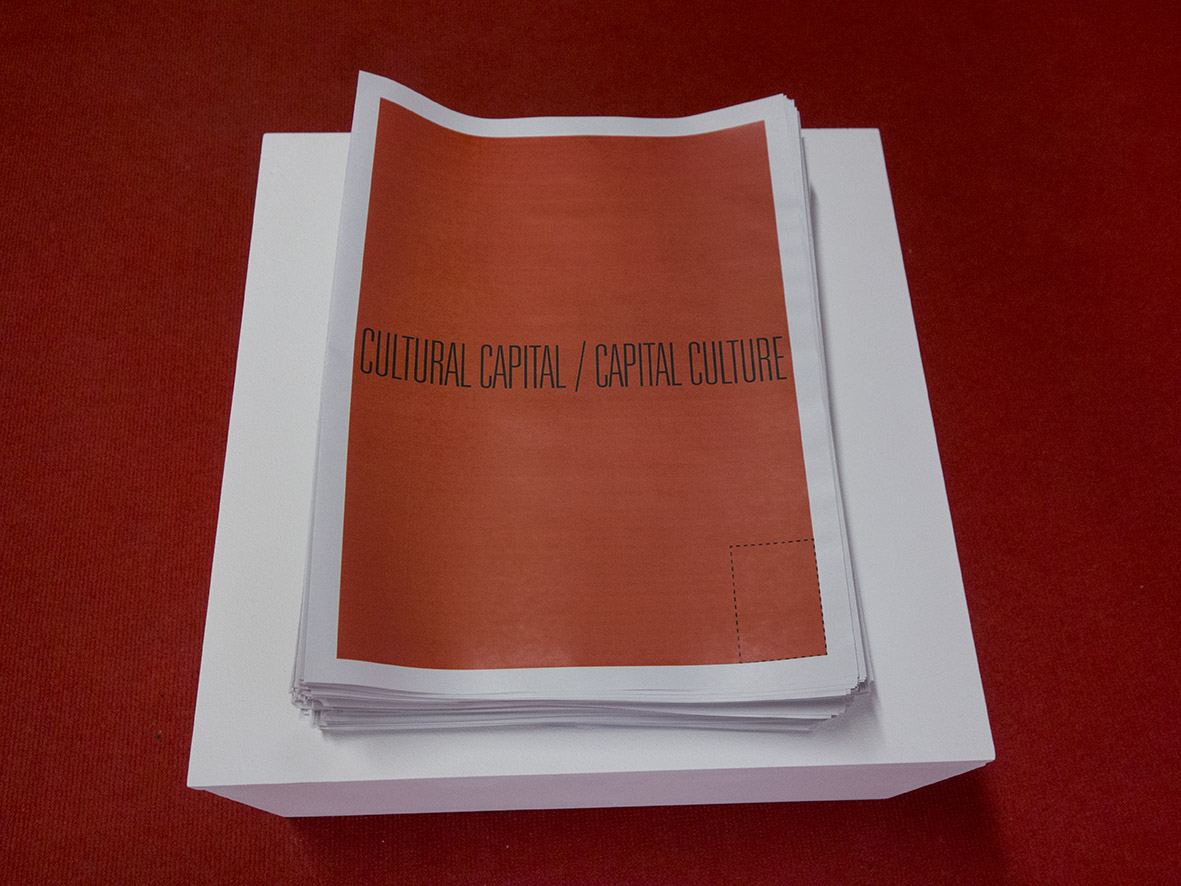

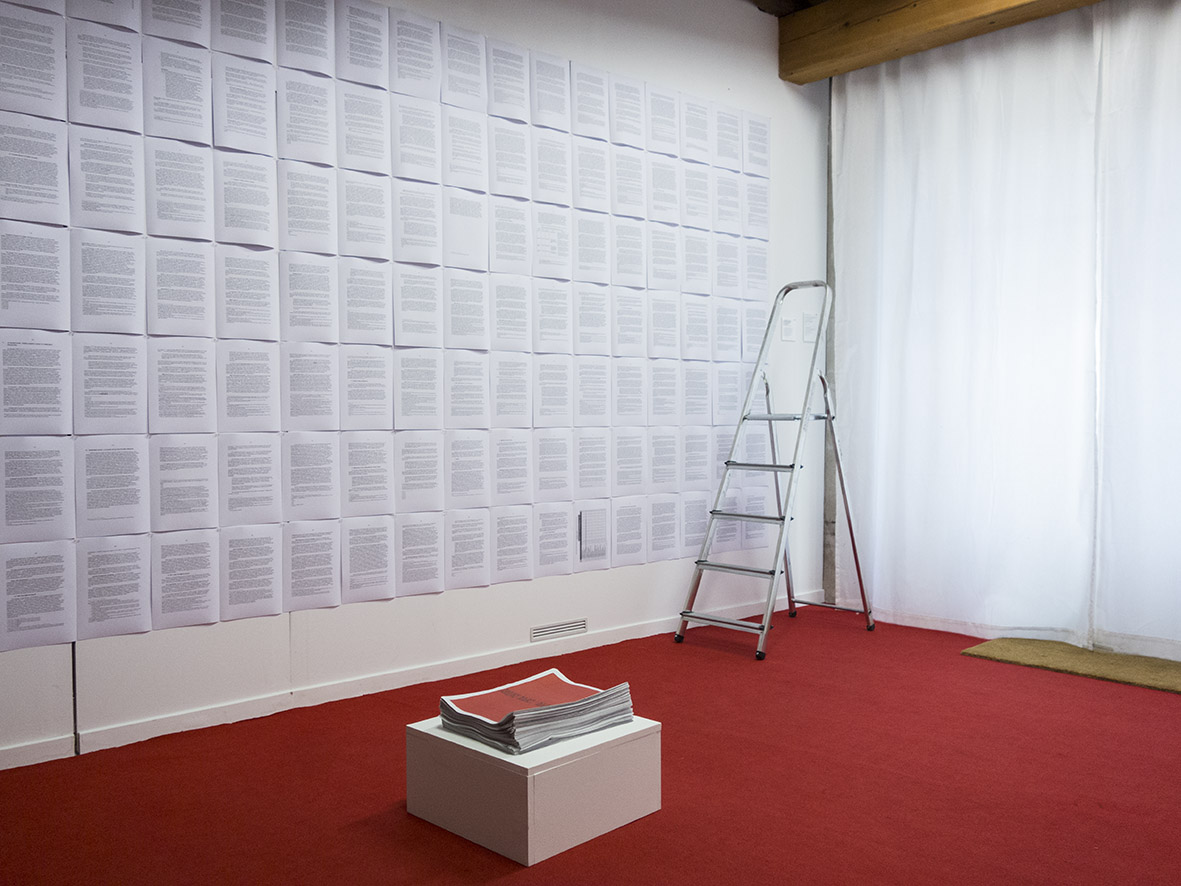

Cultural Capital / Capital Culture

The work

One growing function of contemporary art and cultural production has been to expose its internal structural contradictions. This has been largely due to the fact that its role in representation continues to be problematised and that built-in legacies of power; colonial, institutional, state and corporate, are still complicit in perpetuating inequality despite their support of liberal values. Today’s “bourgeois” culture places a heavy reliance upon corporate capital and as expected with it, a contestation between art, ethics and corporate money.

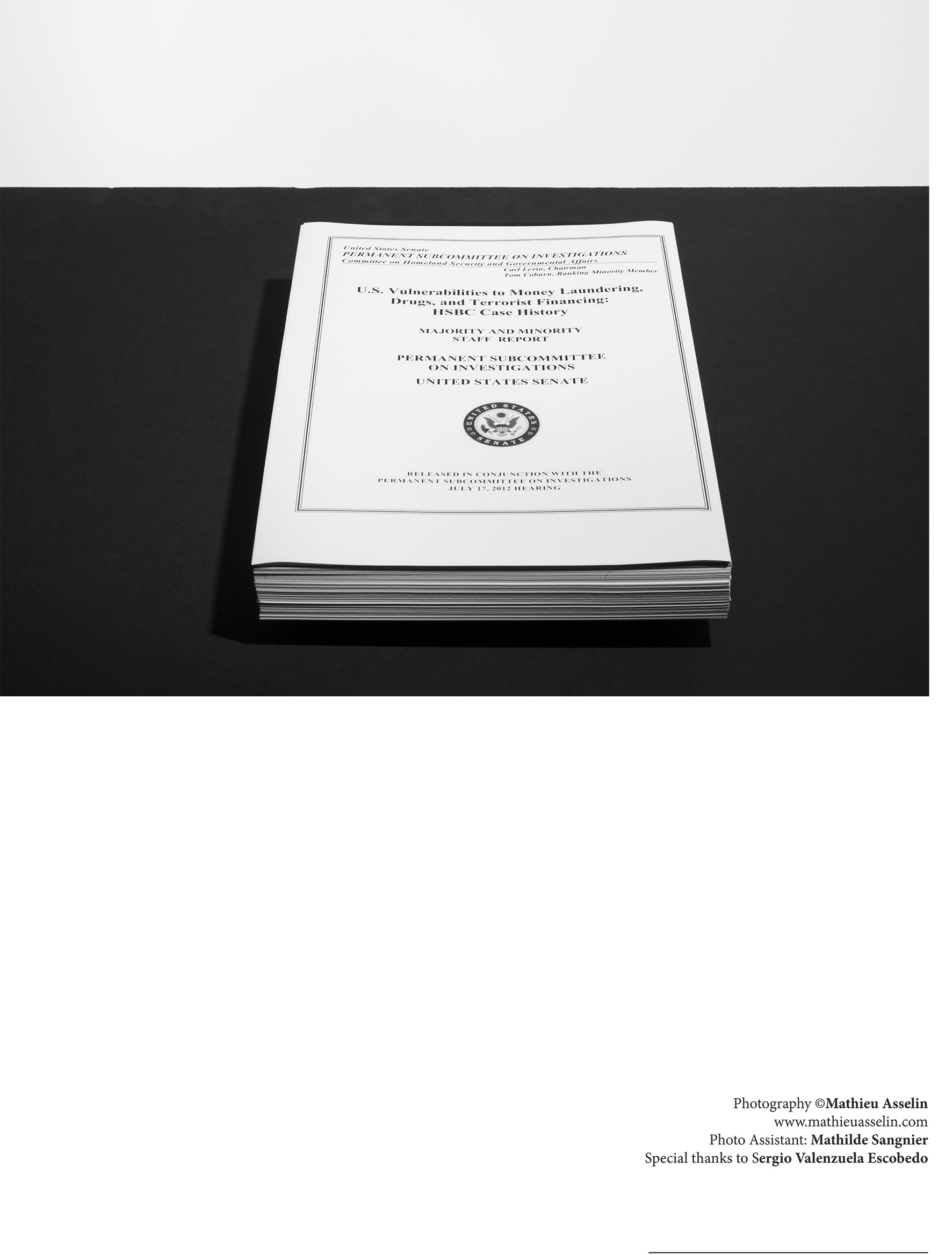

This issue is not confined to the involvement of HSBC, the main sponsor in the Prix HSBC pour la Photographie, but could be levelled against any number of corporate sponsored initiatives and exhibitions across the arts. However, taking this as an example, HSBC, a global banking and holdings company, has since 2012, been under legal scrutiny and charges for money laundering, corruption and malpractice over a number of international banking incidents. The issues around financial misconduct in this context are posited as ethical issues around the nature of corporate business and how this rubs up against liberal concerns deployed through documentary photography and support for emerging artists, whose work may be antithetical to the objectives of a global corporation. As we are aware and what is characterised by the anthropocene; the accumulation of capital sees no ethical grounds in which to halt its disastrous progress across the world. A position at odds with the impression corporate businesses give in support of convivial, light cultural entertainment.

The global nature of art in the 21st Century requires the financial clout of corporate money which is itself a global enterprise. State arts funding although present in Europe, is heavily subsidised by private finance, whereas in the USA, private wealth forms the main source of financial support for the arts. The equation is simple, donations to the arts and cultural sector are rewarded by tax breaks. In addition, alignment with

the arts provides employee perks, brand visibility outside of advertising and perhaps most importantly, the display of care as a respectable society loving company. Corporate money through well-known global firms is perceived to help provide art the audience reach and accessibility it requires, towards a global presence and shared human values.

Other than grassroots arts organisations and artist-led spaces and initiatives, it would seem art without financial backing would be a severely restricted prospect. One would be hard pressed to find major galleries and museums that do not have a portfolio of corporate sponsors and long-term business relationships. Let’s not forget the money that comes from other forms of private support; wealthy trustees, collectors and philanthropists. Without this funding, one cannot see how the scale and shape of the art we see, commissioned and exhibited both at institutions and biennales would be what we know it to be.

State funding is a dual edged sword. On the one hand, there is a public contribution to the arts but on the other, public money requires checks and balances, it requires conformance to a set of values the state sees as its civic responsibility to implement. Diversity targets and pedagogy become prioritised at all costs, at the expense of, ironically, artistic autonomy and freedom. With private money there is the implication of less accountability for the art produced and shown, art for art’s sake perhaps? Having said that one can’t imagine a donor not vetting their artist and the resulting message their art deploys, at least in line with its marketing goals.

This brings us to the artists and photographers that look for support and exposure. In a pursuit that pays little or nothing, artists and art workers are the exploited. Most will never make anything that resembles a living wage for their efforts and when opportunities arise, they are taken. Artists rarely question their own labour and how arts institutions and organisations use and benefit from, the cultural capital they embody. Public and private money and subsequent initiatives are manifest through competitions, awards, commissions, offers of exhibition or publication, residencies and prizes. These are the rewards that lead to legitimisation, industry and peer acceptance, success in the mind’s eye, the promise of future work, the comforting knowledge that one’s efforts are seen.

So, where does the artist stand when the money that provides the platform they need is tainted with any number of contentious issues? Art and especially photography, is often the basis for exploring social injustice, political issues, inequality, conflict, consumerism and people, most of whom are the victims of these conditions. How can artists and their work stand up to critical scrutiny if the conditions which foreground them are complicit in the creation of the subject matter they represent? What does that mean for the integrity of the artist and the ethics of the photo- journalist, documentarian or creative producer who seeks to address our world’s problems? To what extent are artists and photographers, consciously or unconsciously, submitting to the requirements and trends of commodity value, which is now underpinned by the “corporate gaze”, in order to be chosen as worthy of accolade?

The critic Clement Greenberg suggested that art and money were tied through “an umbilical cord of gold”. He may have been right. The notion of art’s commodity value goes beyond the art object as it prefigures art’s very visibility. In light of this, art and its creation, its very presence needs to be transparent if it is to satisfy its self-imposed moral and ethical values. Money can be clean, or it can be dirty, so effort and disclosure are essential if decisions of whether to do “business” are taken or foregone. Organisations need to be wary of corporate money and not cover up concerns or pacify protests that rise against these companies. As artists and photographers, despite the need to make our presence felt and heard, our work needs to maintain its own integrity above anything else. There is always a choice to be made.

Text : Sunil Shah

Curator: Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo

Photo Assistance: Mathilde Sangnier